Shannon needed a lawyer. The Toronto hairstylist was facing a slew of charges, including assault, threatening death, and breaking and entering. As she stood in the courthouse one August 2012 day, she saw a list of lawyers posted in the bail program office.

She picked Toomas Ounapuu.

That choice began a years-long ordeal during which Shannon alleges Ounapuu sexually harassed her. He threatened that she would lose her case and be sent to jail if she didn’t have him representing her, she alleges. With Ounapuu as her lawyer, Shannon was convicted on the criminal charges.

“He made me live in fear,” she says. “He ruined my life.”

Shannon, whose identity is being protected as the alleged victim of sexual abuse, filed a complaint to the Law Society of Ontario in 2019 and the regulator opened an investigation at that time, says her lawyer.

The Law Society made no mention of the allegation or probe to the public.

Not even after a judge overturned Shannon’s criminal conviction in 2022 and gave as his reason: Ounapuu’s “sexually inappropriate comments,” “unwanted hugs” and slaps “on the buttocks” amounted to sexual harassment and his incompetence “was so pervasive that it compromised the fairness of the trial.”

When contacted by reporters, Ounapuu said he disagrees with the judge’s findings and he denied all allegations of improper conduct and sexual harassment.

Finally, in 2024, the Law Society of Ontario, after numerous delays, said it would hold a disciplinary hearing into sexual harassment allegations against Ounapuu. But during the intervening years, the regulator offered Ounapuu’s prospective clients no information about the allegations or judge’s damning characterization of the lawyer’s conduct.

‘Outdated’ level of disclosure puts public at risk

Lawyers who face complaints and regulatory investigations of alleged sexual offences against clients continue to practice law with little or no warning to the public, or mention of the concerns on their public profiles, an Investigative Journalism Bureau/Toronto Star investigation has found.

The Law Society’s public registry makes no mention of criminal charges or non-criminal judicial findings against a lawyer.

The lack of transparency puts the public at risk of being harmed.

The professional regulation committee within the LSO has expressed concern about the regulator’s “outdated” level of public disclosure about its members and their professional records.

The LSO provides “less information about its licensees than most other regulators in the province,” a 2024 LSO committee report says, and the information provided to the public “does not ensure transparency,” and “perpetuates an image of protectionism and a prioritizing of the rights of licensees over the protection of the public.” That lack of transparency exposes clients to the risk of harm “that might otherwise have been avoided” if more information was available.

Earlier this year, the LSO opened a consultation on possible changes to what information about lawyers it makes public. The consultation ends in November.

It marks a potential turning point for the regulator as it confronts what several prominent lawyers say is an unspoken scourge in the profession: lawyers sexually harassing or abusing their colleagues and clients.

In March, following an investigation by the Star/IJB, the head of the LSO said she was “troubled” by the level of sexual harassment, violence and discrimination within the profession, saying the first step to stopping it is “ending the silence and stigma that allows harassment and discrimination to continue.”

The law society says it has already implemented “improved processes for receiving and responding to these complaints,” including a confidential phone line specifically for those wanting to file a complaint about sexual misconduct.

Under consideration are proposals to require licensees to report all criminal charges to the LSO for inclusion on its public registry and a requirement for the LSO to disclose the existence of its investigation into a lawyer’s conduct “if there is a compelling public interest” to do so.

But too often the LSO doesn’t have any information that it could share.

That is because lawyers with reputations for sexual impropriety are often protected by a professional code of silence that deters colleagues from lodging complaints. Many lawyers fear blowing the whistle on a colleague could lead to professional retaliation.

In one case, the alleged conduct of an Ottawa lawyer accused of sexually harassing at least six women over five years was described in court as “an open secret in the legal community in Ottawa if not beyond.”

‘I do not want him to do this to anyone else’

The Law Society has long known of clients complaining of alleged sexual misconduct by their lawyers.

Over the last two decades, the office of the LSO’s Discrimination and Harassment Counsel (DHC) logged 229 complaints from members of the public, including clients, who alleged some form of sexual misconduct.

The informal complaints are anonymous and involve “everything from overtly sexist behaviour, sexually harassing behaviour, stalking, cyberstalking, demanding sex in payment for legal services, all the way through to rape,” says Fay Faraday, who serves as lead lawyer for DHC.

Vulnerable women with low income are conspicuous among those who make “the really egregious” complaints, Faraday says.

Shannon, who took the relatively rare step of filing a formal complaint, had little money when she alleges Ounapuu forced her to pay over $25,000 in legal fees for unnecessary court appearances and demanded she “pay” for his services with in-kind favours like free haircuts at her salon. She alleged to the LSO that she had to sell her furniture to pay her legal bills.

“I do not wish Mr. Ounapuu malice,” reads Shannon’s complaint. “But I do not want him to do this to anyone else.”

Prior to Shannon’s complaint, another woman went to the LSO about Ounapuu in October 2018.

The second complainant alleged that between 2016 and 2018, Ounapuu sent her texts calling her “double D jelly bean” and also said, “If you are good you need a cuddle and if you are bad then you need a spanking.”

The LSO added Shannon’s complaint to its probe. The investigations into Ounapuu have been ongoing for six years.

In an interview, Ounapuu admits to sending text messages to the second complainant but said they were “jokes … taken out of context” and that “I should not have (sent) those texts.”

Shannon says her attempt to hold her former lawyer accountable for alleged misconduct has been tortuous.

“We’re 10 years later. And it’s still going on. He’s still holding me hostage,” she says.

Complaints to law society can idle for years

Ounapuu, who continues to be licensed to practice law in Ontario without restrictions, said delays in the Law Society proceedings were due to resource challenges inside the organization as well as his own health problems that required time extensions to prepare his defence.

At the LSO, which pledges to “act in a timely, open and efficient manner,” a spokesperson said, generally, case complexity and the level of co-operation by the parties can prolong investigations.

Data from a 2024 LSO professional regulation committee report shows in 2023 the Law Society received 6,488 complaints. The average duration for case management from the complaint being made to hearing completion was 1,706 days — or over four and a half years.

The IJB/Star found and reviewed records for 76 cases across Canada, including Shannon’s, that involve a client’s formal complaint about alleged sexual misconduct and that culminated in a regulatory proceeding.

Twenty-seven lawyers faced license suspensions ranging from a few days to a year. Nineteen received minor penalties without interruption to their ability to practice law. Nine faced no discipline and six others were allowed to surrender their licence or resign prior to any outcome. Only 12 had their licence to practice revoked.

These 76 cases are not the only incidents where lawyers allegedly act sexually inappropriately with members of the public. In many cases, complaints never make it to the regulator.

Some allegations are never reported

When principal lawyers at Morphew Symes Menchynski Barristers found out that one of their named lawyers had been in a relationship with their former articling student, the two other lawyers at the small firm swiftly expelled him.

“We treated this as a serious and urgent matter … we viewed the relationship as unacceptable,” said Karen Symes and Anne Marie Morphew in a written statement to the Star/IJB, adding that they had a policy against intimate relationships with members of the firm.

“The explicit reason for his removal was his relationship with our former employee, and the fact that he had deliberately concealed it from us.”

The matter stopped there.

Symes and Morphew said Jenny told them she did not want to be named in a complaint. They also sought legal advice on filing a complaint against their firm’s lawyer to the Law Society.

“We were … advised that (the) conduct did not violate any rules of professional conduct as the Law Society does not have a rule prohibiting intimate, power imbalance relationships … We were told that a complaint to the Law Society would not result in any disciplinary action.”

They did not proceed with a complaint to the Law Society.

Though this case does not involve a client, it underscores one of the ways allegations fail to reach the regulator. It also raises questions about whether the LSO’s ongoing review is tackling all of the key obstacles to transparency and safety for prospective clients, and reveals how reporting of alleged lawyer misconduct is pushed into the whisper network of the legal community.

The young lawyer, Jenny, told the Star/IJB that six months into her articling position she began a relationship with one of her bosses, Andrew Menchynski, that quickly turned.

She says she was pressured by Menchynski to keep the relationship a secret because he feared he would lose his position at the firm if she told anyone and the optics of their relationship would reflect poorly on them.

Like her former bosses at the firm, Jenny did not complain to the Law Society. She feared it could lead to reputational damage and retaliation from Menchynski, who was a distinguished Toronto lawyer. Jenny, who has been given a pseudonym in this story, has since left law.

Menchynski declined to comment. His lawyer, Peter Downard, said, “This was a personal and consensual relationship between two adults.”

Disclosure about lawyers lags other Ontario professions

While the regulator’s ongoing review focuses on what information it could include on lawyer’s public profiles, the LSO does not appear to be considering whether firms should be obligated to report inappropriate relationships to the regulator. Nor does it appear to be considering a stricter policy on sexual relationships between lawyers and colleagues or clients.

While the current Law Society rules say sexual harassment of clients is not permitted, the code of conduct simply advises lawyers to “carefully consider” any sexual relationships with clients “in order to determine whether a conflicting personal interest exists.”

That doesn’t go nearly far enough, says Erin Durant, founder of Durant Barristers in Ottawa.

“I do professional regulation work and disciplinary work in other professions. For doctors and other regulated health professions it’s an outright ban.”

Health professionals also have information about criminal charges reflected on their public profiles.

Not so for lawyers.

In September 2022, Menchynski, by then working as a sole practitioner, was charged with assault, forcible confinement and possession of a weapon (he was allegedly holding a butcher’s knife) against an intimate partner.

The woman also filed a complaint to the Law Society regarding Menchynski’s alleged assault.

Days before she filed her complaint, Menchynski asked the woman what he could do to “help convince [her] not to try to get me fired,” according to text messages provided to the Law Society and reviewed by reporters.

He wrote: “If I have an income stream, I am still hoping to provide you $500 support per month.”

Menchynski, through his lawyer, did not respond to questions about the financial offer to the woman.

The Star/IJB have learned that Menchynski entered a secret undertaking with the Law Society in March 2023 requiring him to meet certain conditions to practice. Details of Menchynski’s undertaking are confidential because they contain personal health information, a LSO spokesperson said.

In August 2023, Menchynski entered a 12-month peace bond, and the criminal charges were withdrawn.

“Mr. Menchynski has steadfastly denied the allegations made by the complainant …[and] entered into a peace bond without admitting to the facts that gave rise to the charges,” Menchynski’s lawyer Downard said in his statement.

On the LSO’s website, Menchynski’s public profile says he is currently “suspended administratively.”

There is no mention of his criminal charges, his undertaking or the peace bond.

It is not clear when the regulator’s investigation into the initial complaint will be completed.

Lawyer accused of proposing services in exchange for sex

When Leanne Aubin hired Ottawa criminal defence lawyer James Bowie in August 2022 she did not know that the Law Society had already been investigating him for nearly a year without public notice.

At the time, he was the subject of five investigations concerning allegations including problematic billing practices and failing to serve clients, and had recently been suspended administratively for failing to pay his Law Society dues.

Bowie was also the subject of industry gossip, according to a judge’s decision in 2022, in which he summarizes descriptions of Bowie’s alleged conduct with women as “predatory” and an “open secret” in Ottawa’s legal community.

But as far as Aubin — or any member of the public — could tell, Bowie had a spotless record.

The LSO’s ongoing transparency review is exploring whether the regulator should publicize details of its own investigations as they are ongoing, “if there is a compelling public interest” to do so.

Aubin says the problems started when she proposed paying Bowie in $200 installments on her biweekly paydays, in lieu of an upfront retainer. Bowie agreed, but with a condition, she alleges.

“He messaged me expressing that he found it really sexy that I have a split tongue and that he wondered what it would feel like on his penis. If I wasn’t able to make a payment on time he wanted me to agree to then give him fellatio,” she says.

Aubin alleges that Bowie said he was friends with the Crown attorney prosecuting her case, “and that if I told anybody he would throw my case and get me charged.”

For weeks, Aubin says Bowie messaged her so “frequently and aggressively” with sex-for-legal-service propositions she became afraid for her safety.

Aubin says she was completely vulnerable to Bowie and was left feeling suicidal. “Your lawyer is literally somebody you’re supposed to trust with your life. He was threatening to essentially ruin my life.”

Bowie told the Star/IJB that Aubin’s allegations are “false,” and claims they were concocted by another lawyer who Bowie describes as a “political opponent.” Bowie says the allegation that his conduct was an open secret in Ottawa legal circles “is a fiction.”

Aubin found a new lawyer, Michael Spratt. By mid-September her assault charges were dropped. Then Spratt helped her submit a sexual harassment complaint to the LSO in September 2022 detailing her experience with Bowie.

Aubin went public with her complaint soon after. Since then, Spratt says, 25 more women have contacted him with complaints about Bowie.

‘An offence to the court’s sense of decency’

In April 2023, Bowie was criminally charged by Ottawa Police for alleged death threats against Aubin, attempting to buy a firearm illegally and attempting to “obtain an act of oral sex” from her, according to court documents. None of these allegations has been proven and the case remains before the courts.

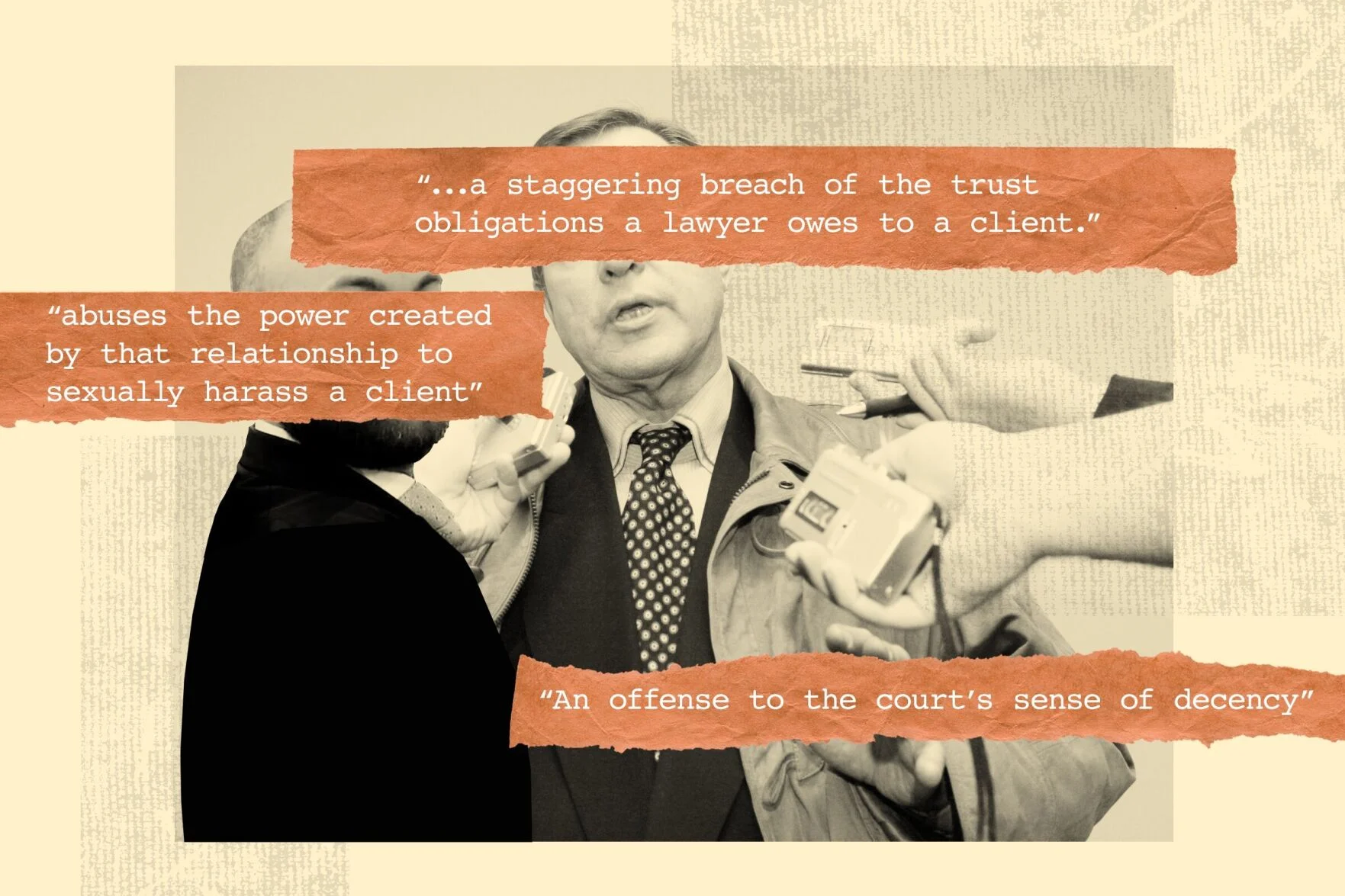

Aubin also sued Bowie. On Oct. 11, an Ottawa judge ordered Bowie to pay Aubin $235,000, calling his conduct “a staggering breach of the trust obligations a lawyer owes to a client.”

Bowie failed to mount a defence to the lawsuit, saying in court documents that health problems hindered his ability to respond to the case in a timely manner.

As a result, the judge made what’s known as a default judgment.

Bowie’s conduct was “an offence to the court’s sense of decency,” the judge ruled, adding that Bowie “harmed not only the plaintiff but the reputation of lawyers generally.”

Aubin’s complaint against Bowie is one of the six sexual harassment complaints currently under investigation by the Law Society of Ontario. In all, Bowie is the subject of 12 Law Society investigations into client complaints about “service, integrity and handling of client trust funds,” according to the LSO’s filings in court.

Bowie’s public profile states he is suspended for not participating with LSO investigations. It makes no mention of the sexual harassment allegations or the civil judgment.

This Story was also publishd in the Toronto Star.

The Investigative Journalism Bureau is an impact-driven, collaborative newsroom that brings together professional and student journalists, academics, graduate students and media organizations to tell deeply-reported stories in the public interest.

Your support is crucial to our mission. By donating, you help us continue to uncover the stories that drive meaningful change and hold power to account. Join us in our commitment to high-quality, independent journalism.

- Behind the Reporting: Emma Jarratt on Cracking the Code of Silence - 27 June 2025

- What the Law Society of Ontario isn’t telling you about your lawyer - 25 June 2025

- ‘I am deeply troubled’: Head of Ontario law society speaks out after Star/IJB investigation into sexual harassment among lawyers - 25 October 2024